Apartheid Ends

Frederik de Klerk and Nelson Mandela in 1992. (Creative Commons photo. Attribution to author and info can be found here)

When President Botha suffered a stroke he chose to quit for his health (1989) and F.W. de Klerk became the new President in his place. De Klerk was extremely conservative and had no real interest in changing Apartheid, but realized that there was nothing he could do based on international pressure. He made the decision to release Mandela from house arrest in an effort to make his government look better. His release was broadcast all over the world due to the sheer number of people who had gotten involved in the movement. He was filmed walking down the road towards his wife and kids. When he reached the end he gave a speech about peace, but made it clear that the struggle was far from over.

The policy of Apartheid was dismantled in a series of negotiations between the ANC and the National party (1990-1993). While there were a good deal of people involved in these negotiations, the power really lied with Mandela and de Klerk. This is often portrayed as if the end of the system was already decided on, but this is actually far from the case. The government wanted to know if it was even possible to find a middle ground that the two sides would be able to agree on, and were quite hesitant to claim that the deal was agreed to before they saw this was possible. Mandela knew that this was the case when it came to the government, but he had his own ideas on what needed to happen. He was extremely polite during the negotiations, however, he was

firm about what he wanted and his unwillingness to budge on certain issues upset some people. Keep in mind that the people in this room weren’t used to black South Africans having this much power. They were used to being able to dictate to the people, so his strong stance bothered people who weren’t used to this.

Violence broke out among the general population on a few occasions during these negotiations, which made the talks much more tense than before. Mandela spoke out and asked the people to stop the violence during this sensitive time on a couple of occasions. This violence was actually quite helpful for his negotiations though, showing the government what they were in for if a deal couldn’t be worked out. The largest demonstration was by the Zulu nationalist group called the Inkatha Freedom Party, who committed a massacre known as the Boipatong Massacre (1992) in which 46 people were killed. The ANC accused the government of staging this attack for political purposes and walked out of the negotiations due to this. Negotiations would restart that same year after the Bisho Massacre where 28 ANC supporters were shot at a protest. The government knew how bad this looked for them so they worked with the ANC to get negotiations back on track. The next year 11 people were killed by the ANC while attending church in Cape Town. They did arrest and jail one person for the St. James Church Massacre, but had to release him when they realized it wasn’t him who had done it.

The negotiations ended when the two sides agreed on free and open elections for all people in South Africa. This was a seismic shift in South African politics due to the fact that the white people in the country were a huge minority, so this in effect was them giving up power. Both Mandela and De Klerk would win the Nobel Peace Prize in a landslide due to their work together (1993). In free elections the next year, the ANC would win in a landslide of 62% of the votes and Mandela would be named the first president of this new version of the country. He garnered international respect for making sure that the government didn’t try to punish the white community for their previous actions. While there were a lot of calls to do that, the leadership of Mandela kept this from happening at this key stage in the country’s history.

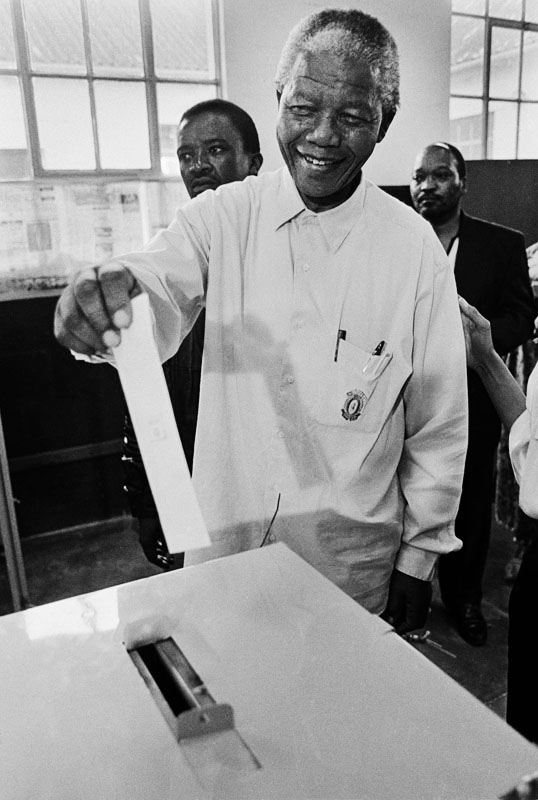

Mandela voting in 1994. (Creative Commons photo. Attribution to author and info can be found here)