South African Response To Pressure

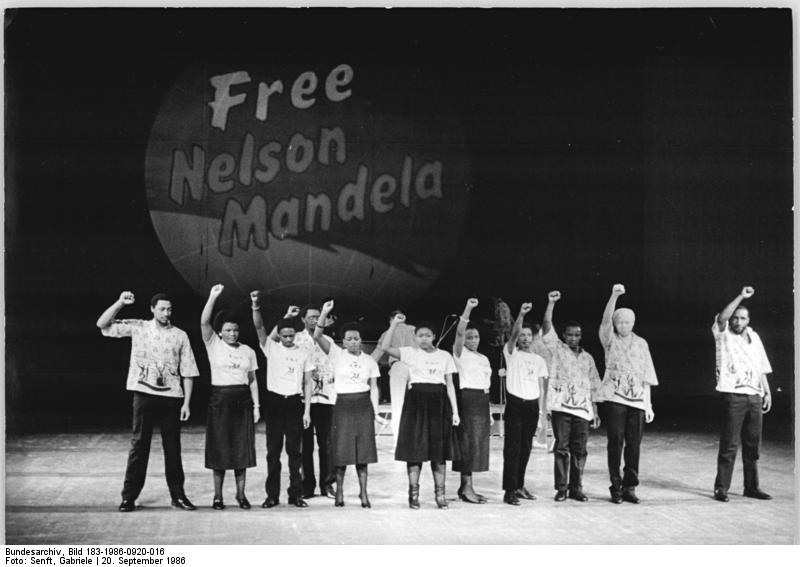

A Free Mandela protest in Berlin. Photo by Bild Bundesarchiv (Creative Commons photo. Attribution to author and info can be found here)

While the South African regime was dealing with pressure from multiple angles, the version of pressure that hurt them the most was the boycotts against them. They had been an economic powerhouse in the 1960’s, but had stalled and had one of the worst growth levels on earth by the late 1980’s. On top of that, they were watching countries all over Africa lose to the rebel movements in their own countries. The situation for South Africa was looking more and more untenable as the years progressed.

The South African government supported their policies by claiming they were trying to protect the white population, but often referred to it only as providing security for all people. The majority of white South Africans felt they were besieged by communists and black nationalists, and felt their back was against the wall. The repercussions on any activism within the townships were punished harshly, with jail and whippings the most used tactics. In fact, between the years of 1982 and 1983 the police whipped 40,000 people for “rebel” activities, which often times just meant they weren’t completely caving to every demand of the police. These actions caused young people to move towards violence more often, and the ANC started to set off bombs in civilian areas, killing and maiming civilians and government officials.

The government tried to calm this by giving voting rights to other racial groups in 1984. They gave each group their own house in parliament (including Indians), but the system was rigged to make sure that the white government officials could always outvote them. At the same time, though, the government was launching raids across their borders against what they believed to be ANC training camps in nearby countries. They even sent mail bombs to targeted ANC officials in Europe to get rid of them. When it was clear that the rebels weren’t backing off, the country called a state of emergency again and took rights away from the other groups (1985). People were thrown in jail without trial and tortured by the thousands under this new policy. The government also forced censorship on the press and spread propaganda to the whole country.

President P.W. Botha would be the first major government official to seriously consider changing the policies of Apartheid due to the pressure. He moved Mandela out of prison and into house-arrest in the hopes of starting discussions for changes. A big part of this was a public relations decision though, hoping to show that this leader with a worldwide following was being treated well by the government. He did make some positive changes by raising funding for black schools and repealing marriage laws, but it wasn’t as revolutionary as many hoped. For instance, he raised funding for schools from 1/16th of what white schools got to 1/7th, which was a big jump, but still a long way from equality. At one point during the discussions between Mandela and Botha he agreed to release Mandela if he agreed to speak out against the violence that was happening, but Mandela denied this request and made it clear that the violence was the responsibility of the government. Mandela was quite clear that he didn’t want to be used as a propaganda tool by the government, claiming that if they simply gave true democracy all of these issues would end.

A view of Robben Island from a nearby mountian. (Creative Commons photo. Attribution to author and info can be found here)

The cell that Mandela stayed in during his time. (Creative Commons photo. Attribution to author and info can be found here)